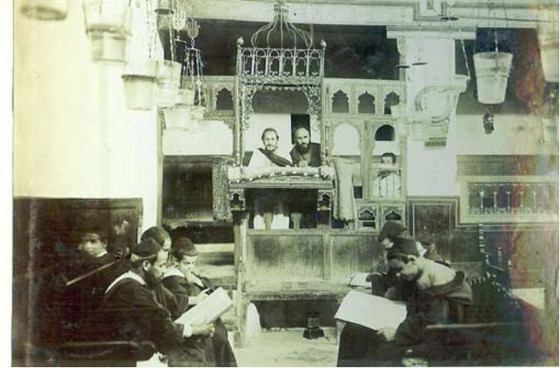

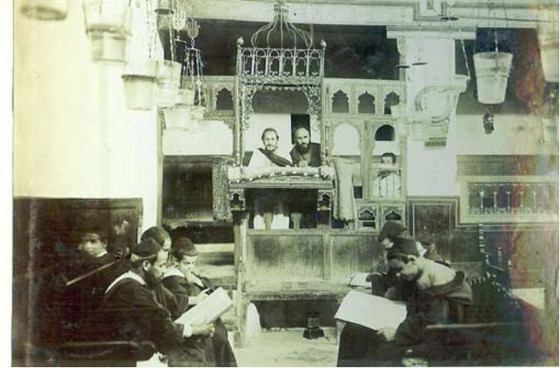

SYNAGOGUE DANAN À FÈS

| Numéro d'objet: |

28766 |

| Photographe: |

Burchardt Hermann |

| Date: |

1905 |

| Catégorie: |

Photographie |

| Origine: |

Fès |

| Thème: |

Synagogues |

Recherche dans "Notes":

La synagogue Aben Danan (Fès)

Adossée à l'enceinte mérinide, dans la rue Farran Tahti, la synagogue Aben Danan fait partie d'un ensemble résidentiel comprenant deux habitations à l'étage et deux entresols. Elle est l'un des joyaux de la culture juive et un espace religieux privilégié du judaïsme marocain. Fondée par Mimon Boussidan, originaire de Zaouiat Ayt Tshaq, au milieu du 17ème siècle, elle est depuis 1812 dans le patrimoine de la famille Danan, date d'une première cession de parts.

Ce monument a été désaffecté depuis 1969 jusqu'à sa restauration en 1997.

Tant le décor que le plan de l'édifice sont redevables à l'art islamique et montrent que les productions artistiques ne peuvent être envisagées hors de leur contexte géographique et culturel. Classée patrimoine universel mondial par l'UNESCO, la synagogue Aben Danan fut la première à être restaurée pour son rôle prépondérant dans la culture et la religion juive à travers tout le Maghreb ainsi que dans l'avènement des réformes. Si elle n'est plus utilisée comme lieu de prière, elle revit à présent en tant que synagogue-musée agrandie pour les visites culturelles et touristiques.

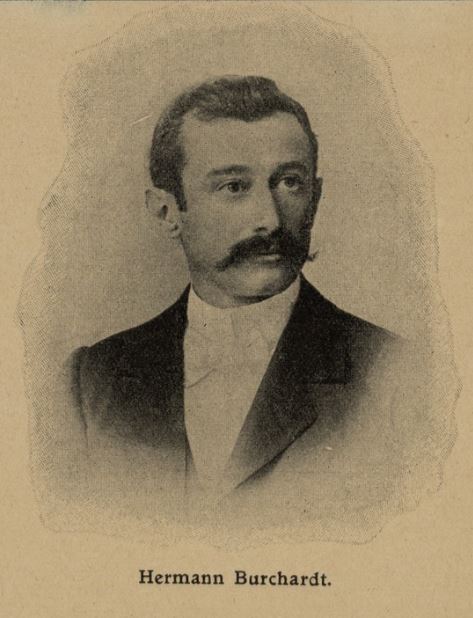

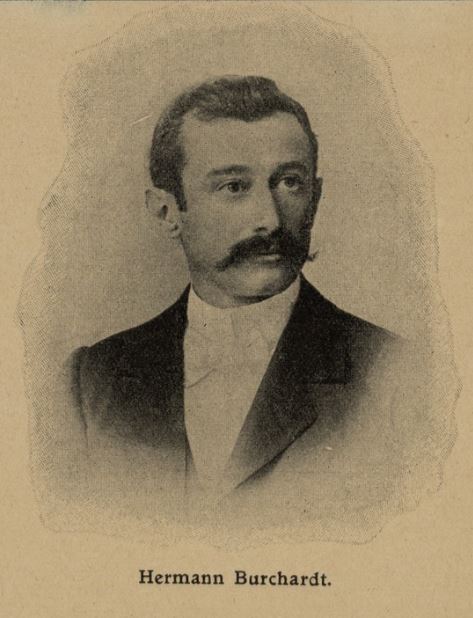

Hermann Burchardt (1857-1909)

In the 19th century, a young German-Jew who had just turned thirty, decided to leave the family business and set off on a journey around the world that would incorporate two of his great passions: photography and the study of ancient and exotic peoples. Hermann Burchadt decided to use his substantial inheritance to rent an apartment in Damascus that would serve as the base for his research expeditions and adventures. He had already studied Arabic and Turkish which he hoped to use to his advantage. Even before he set off on his travels, Burchardt saw himself as a citizen of the world, a man without limits, able to reach places no European had ever set foot before. On one of his journeys, in 1901, he encountered just such a place. In the middle of the harsh and barren desert he reached the city of Sana'a. On his wanderings around the hilly capital city he was stunned by a group of people he encountered—members of the Sana'a Jewish community, whose ties to other Jewish communities in the world had been almost completely severed for generations.

Together with his large entourage, Burchardt spent almost a year with the community. He got to know them personally, to study and document their customs, listen to their unique life stories, transcribing almost every word in his diary, and for the first time in history, he photographed them.

The article he published in the journal Ost und West included the spectacularly beautiful first-ever photographs of the Yemenite Jewish community. The images were nothing short of a revelation for European Jewry. After a break of thousands of years there was at last a tangible sign of the existence of the Yemenite Jewish community. It seemed as if the world's most authentic Jew, who had lived completely isolated from any foreign influence, had finally been found (at least this is what they believed in Europe). The article so excited the journal's readership that the photographs were turned into postcards which were sold and circulated by the thousands.

Is this how Jews looked before the Exile? Are these the Jews of the Second Temple? For those who had been overwhelmed by the encounter with the Jews of Eretz Israel, the West's encounter with the isolated and remote community of Sana'a was even more astonishing. They wanted to examine the authentic Yemenite siddur, to analyze the differences between their and “our” biblical traditions, and essentially, every tiny scrap of information about their unique customs.

In 1909, while Burchardt was escorting the Italian consul on his way from Sana'a, the adventurous and learned ethnographer convinced the consul to take a route that had never before been travelled by a European. The grand convoy was ambushed and the desert thieves' plans went terribly wrong: Hermann Burchardt and the Italian consul were killed.

At his funeral, Burchardt was eulogized by an Italian merchant who had befriended him on his last visit to Sana'a. He said that the Jews of Sana'a, a community close to the famous adventurer's heart, were mourning his death.